Section Abstract Introduction Methods Results Discussion Conflict of Interest Acknowledgment References

Clinical Research

Prevalence and pattern of domestic violence at the Center for Forensic Medical Services in Pekanbaru, Indonesia

pISSN: 0853-1773 • eISSN: 2252-8083

https://doi.org/10.13181/mji.v26i2.1865 Med J Indones. 2017;26:97–101

Received: February 13, 2017

Accepted: May 03, 2017

Author affiliation:

1 Department of Forensic and Legal Medicine, Faculty Medicine, University of Riau, Riau, Indonesia

2 Faculty Medicine, University of Riau, Riau, Indonesia

Corresponding author:

Dedi Afandi

E-mail: dediafandi4n6@gmail.com

Background

Domestic violence (DV) is still a significant public health problem, especially in women’s health. Few studies have reported the prevalence and domestic violence in Indonesia. The aim of this study was to identify the prevalence, type of violence, and forensic examination on domestic violence victims in emergency departments.

Methods

This study was a retrospective analysis of domestic violence victims observed in the Emergency Department at the Bhayangkara Hospital, Pekanbaru, Indonesia, between 2010 and 2014. The determinations of DV cases are based on the medico-legal reports (visum et repertum) and the police’s official inquiry letters.

Results

Out of 6,876 medico-legal injury reports of living victims were reviewed, and 755 (10,9%) cases were DV. The majority of victims in DV were women (93.8%) with childbearing age group as the highest frequency (77.9%). Most of the DV victims were housewives (67.0%). Moreover, physical assault was the most common DV types (98.7%). Bruise was the predominant type of wound among the DV victims (76.2%), and almost half of the victims had abrasions (48.1%). Head and limbs were the predominant sites of wound. Blunt injury was found in more than three-quarters of the victims (88.5%).

Conclusion

The prevalence of domestic violence was high among living victims in the emergency department, with women as the majority of victims.

Keywords

domestic violence, forensic examination finding, prevalence, women, wound

Domestic violence (DV) is a type of violence in the household. DV is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as any behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological, or sexual harm.1 The perpetrator belongs to the victim’s “domestic environment”: an intimate partner, husband, former intimate partner, family member, friend or acquaintance in a domestic setting.2

Women are more likely to be victims. DV is more likely to be a form of violence against women due to the number of women as victims. A WHO study concluded that the proportion of women who had ever suffered physical violence ranged from 13% to 61%, and sexual violence ranged from 6% to 59% was done by a male partner.1 The WHO reported that the global prevalence of physical and sexual intimate partner violence is 30%, with the highest prevalence in the South-East Asia. DV is associated with physical, mental, sexual and reproductive health.1,3,4 Data showed that 42% of victims received physical injury from their partner. Effects on mental health include depression and alcohol use disorder. Mortality is caused by homicide by partner and suicide by themselves.3

Generally, Indonesia lacks of national data on DV. Few studies have reported on the prevalence of DV in Indonesia. Hayati et al5 reported that the prevalence of lifetime exposure to sexual and physical violence was 22% and 11% was among women in rural areas. There is no data regarding the prevalence of DV in urban areas. Pekanbaru is the capital city of the Riau Province, one of the 34 provinces in Indonesia. This city is the third largest (inland) urban area on the Sumatra Island with a population of approximately 1.2 million people. The aim of this study was to identify the prevalence, type of violence, and forensic examination finding in domestic violence victims in Emergency Department of Bhayangkara Hospital Pekanbaru (BHP). This hospital is a teaching hospital of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Riau and the hospital center for forensic medical services in Pekanbaru. All DV cases reported to the police will be referred to the Bhayangkara Hospital Pekanbaru.

METHODS

A retrospective descriptive study was conducted at the BHP. All medico-legal injury reports of living victims from January 1st 2010 to December 31st 2014 were studied for the prevalence of DV by using basic data, such as sex, age, profession, type of domestic violence and basic forensic parameters (type, number, site of wound and type of injury). The determinations of DV cases are based on the medicolegal report (visum et repertum) and the police’s official inquiry letter. The completeness of the data obtained by collecting and recording the necessary data that contained in the visum et repertum of DV cases. The research protocol was approved by the institutional research committee of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Riau (No. 52/UN19.1.28/UEPKK/2015).

RESULTS

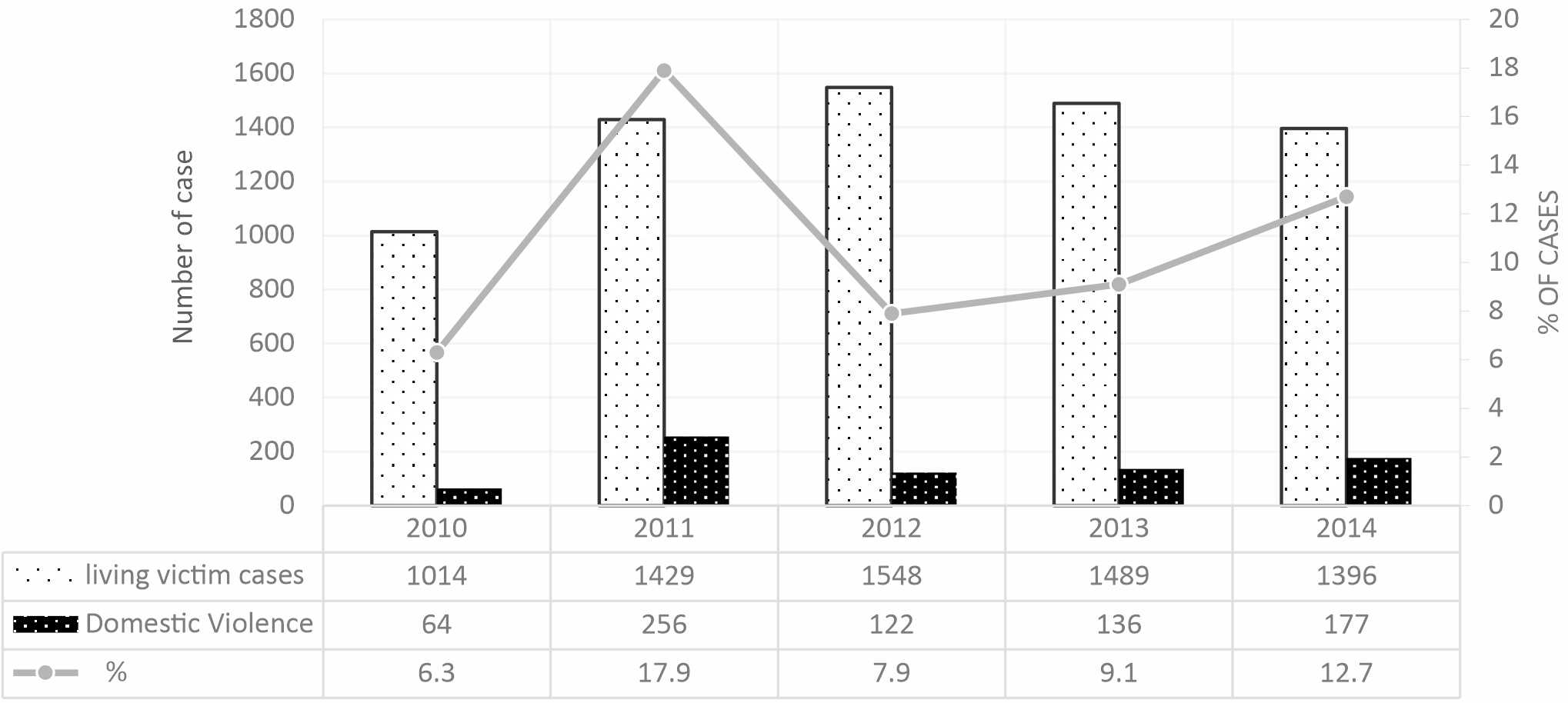

A total of 755 cases were identified for inclusion in this study. Overall, the total number of medicolegal injury reports of living victims in the BHP over the study period was 6,876. The domestic violence percentage of all cases of living victims was 10.9% and varied from 6.3% to 17.9% per year (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The number of living victim cases, domestic violence victims, and percentage by year

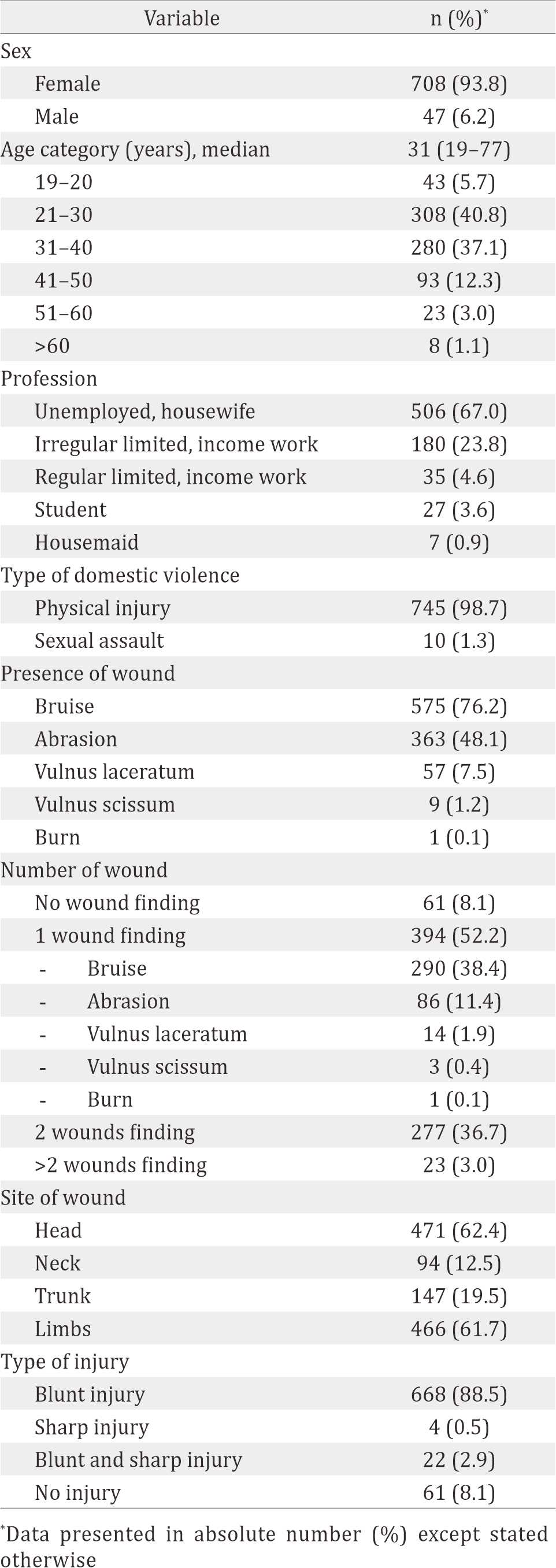

Almost all of the DV victims were women (93.8 %). The ages of victims ranged from 19 to 77 years old, with a median of 31 years old. The largest age-groups were between 21–30 years and 31–40 years. The age-group of 21–40 years comprised 77.9% of DV victims. Most of the DV victims were housewives (67.0%), in which seven DV victims (0.9%) were housemaids (Table 1).

Physical assault was the most common DV types (98.7%). Bruising was the predominant type of wound that presented among DV victims (76.2%), and almost half of the victims had abrasions (48.1%). One number of wound was found in more than half of victim (52.2%). Head was the most common location of wounds (62.4%) followed by limbs (61.7%). More than three-quarters of victims (88.5%) reported that the type of injury was a blunt injury (Table 1).

Table 1. Distribution of demographic, type of violence and injury pattern of domestic violence victims (n=755)

DISCUSSION

A study regarding the prevalence of DV among living victims who attended the emergency department in Western countries reported a prevalence of DV cases: 1.1% in the United Kingdom (UK)6 and 4–6.6% in Northern Ireland.7 The prevalence of DV in eastern countries has been largely restricted to reports and estimates. The prevalence of DV in this study was higher than the previous study in the UK and Northern Ireland. These differences might be related to methodological differences and the sociodemographics of the victims, such as gender norms, culture, marital status, ethnicity and education gap.2,5,8

Our study showed the prevalence at the emergency department was lower compared to prevalence in population based study. Several population-based studies reported that the prevalence of DV was 56% in Eastern India,9 and 26.4% of women and 15.9% of men in the United States (US).10 Globally, the WHO estimates a prevalence of lifetime physical and or sexual violence for women ranging between 24.6% in the Western Pacific to 37.7% in South-East Asia.3 This difference could be explain because in initial studies, most women refrain to report their physical assault and or sexual violence due to traditional gender norms, subordination from their spouse, education, taboo, fear of not being believed, not being asked if they had been affected by domestic violence, especially by health professionals, fears of reprisal, and feelings of love, shame, and guilt.2,3,5,7,9

Our study revealed that almost all DV victims were women (93.8%). This result is similar to many studies about violence against women. This is reasonable because DV is a different form of violence again women related to gender-based violence.1–3,11 The results of this study indicated that the phenomenon of violence against women in rural areas5 also occurred in urban areas. This study further reinforced that woman’s position is still subordinated from man in Indonesia. Forty-seven (6.2%) men were victims of DV in our study. Another study showed a higher number of men as DV victims, 11.5% in Portugal12 and 22% in Greece.13 This can be explained due to greater gender equality in Western compared to Eastern countries. The findings in this study indicated that both men and women could be victims of DV. However, given the smaller number of male victims in this study, more attention should be given to female victims of DV in Indonesia.

The peak incidence of DV occurred in the childbearing age groups (77.9%), the age group 21–40 years (40.8%) and the age group 31–40 years (37.1%). Another study reported 65% in Hong Kong,14 while the WHO estimated 31.1%– 36.6% for five years for each group in the age group 20–39 years.3 The profession of most of the DV victims in our study was housewife (67%), which was higher than the study in Greece (32.2%).13 Meanwhile, a population-based study in Eastern India reported is 80%.9 From our study, we found seven housemaids that were DV victims. Murty15 reported two cases of maid abuse in Malaysia. According to the Indonesian’s Elimination of Domestic Violence Act,16 a housemaid who receives violence from their employer or member of their house could be a DV victim.

Almost all of the DV victims in our study had physical injuries (98.7%) compared to sexual assault (1.3%). The prevalence of sexual assault in this study was lower than the prevalence of DV from other studies, in Indonesian rural areas (22%)5 and Eastern India (19.7–32.4%).9 Only a few women who were sexually assaulted would report it to the authorities due to taboo and religious reasons. Based on the Indonesian Penal Code, sexual assault is defined as a sexual violence occurs outside marriage. In the Indonesian’s Elimination of Domestic Violence Act,16 sexual assault is categorized as one type of DV. However, the Indonesian Council of Ulama declared that sexual assault in marriage can be considered as DV if the husband coerces sexual intercourse in conditions that are prohibited syar’i: if the wife is in a state of menstruation and childbirth or during Ramadhan fasting, religious pilgrimage, anal sex, and if the wife is ill.

Our study reported that 76.2% of victims had bruises, followed by abrasions (48.1%). The combination of wounds was found in less than half of the victims. This result is similar to another study in Turkey17 that reported that most DV victims had soft tissue lesions. More than 60% of wounds were on the head and limbs, in conjunction with the study in Greece (75% in limbs, and 50% in head).13 The most common type of injury was blunt force injury (88.5 %), and only 0.5% was caused by a sharp injury. This finding is similar to a study in Turkey (0.7%).17 The findings of this study indicated that DV could lead to morbidity for the victims.

The limitation of this study is that the prevalence of DV is not indicative of the real magnitude of the number of cases of DV. However, the results of this study could add to our knowledge regarding the magnitude of the DV problems, as well as the importance of medicolegal aspects of DV. This study may also add to our overall understanding of the problem and may help to identify patterns or trends in DV, especially among urban areas and the childbearing age population group and may assist in implementing effective preventative measures.

In conclusion, the prevalence of domestic violence is high among living victims in the emergency department, with women as majority of victims. Almost all victims experienced physical assault. Bruises and abrasions were the most types of wound with head as the common site. Blunt injuries were also mostly found in domestic violence victims.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors affirm no conflict of interest in this study.

Acknowledgment

We thank the Director of Bhayangkara Hospital Pekanbaru, administrative staff of Medicine and Health Department Riau Regional Police for their assistance in collecting medico-legal report.

REFERENCES

- García-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts C. WHO Multi-country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence against Women Initial results on prevalence, health outcomes and women’s responses Full Report. World Health. 2005. p. 13–40.

- Flury M, Nyberg E, Riecher-Rössler A. Domestic violence against women: Definitions, epidemiology, risk factors and consequences. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140(w13099):2–7.

- www.who.int [Internet]. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. [update 2013; cited 2017 Feb]. Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/ publications/violence/9789241564625/en/

- Hegarty K. Domestic violence: the hidden epidemic associated with mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 2011;198(3):169–70.

- Hayati EN, Högberg U, Hakimi M, Ellsberg MC, Emmelin M. Behind the silence of harmony : risk factors for physical and sexual violence among women in rural Indonesia. BMC Women’s Health. 2011;11:52.

- Boyle A, Todd C. Incidence and prevalence of domestic violence in a UK emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2003;20(5):438–43.

- Stevenson TR, Goodall EA, Moore CB. A retrospective audit of the extent and nature of domestic violence cases identified over a three year period in the two district command units of the police service of Northern Ireland. J Forensic Leg Med. 2008;15(7):430–6.

- Bazargan-Hejazi S, Kim E, Lin J, Ahmadi A, Khamesi MT, Teruya S. Risk factors associated with different types of intimate partner violence (IPV): an Emergency Department Study. J Emerg Med. 2014;47(6):710–20.

- Babu BV, Kar SK. Domestic violence against women in eastern India: a population-based study on prevalence and related issues. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):129.

- Breiding MJ, Black MC, Ryan GW. Prevalence and risk factors of intimate partner violence in eighteen U.S. States/Territories, 2005. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(2):112–8.

- Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002;359(9313):1232–7.

- Carmo R, Grams A, Magalhães T. Men as victims of intimate partner violence. J Forensic Leg Med. 2011;18(8):355–9.

- Kosmidis G, Vlachomiditropoulos D, Goutas N, Spiliopoulou C. Medico-legal aspects of family violence cases in Athens, Greece. Int. J. Caring Sci. 2014;7(2):488–96.

- Chan KL, Choi WM, Fong DY, Chow CB, Leung M, Ip P. Characteristics of family violence victims presenting to Emergency Departments in Hong Kong. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):249–58.

- Murty OP. Maid abuse. J Forensic Leg Med. 2009;16(5):290–6.

- www.ditjenpp.kemenkumham.go.id [Internet]. Undang- Undang Nomor 23 Tahun 2004 tentang penghapusan kekerasan dalam rumah tangga. [update 2017; cited 2017 Feb]. Available from: http://ditjenpp.kemenkumham. go.id/hukum-pidana/653-undang-undang-no-23-tahun- 2004-tentang-penghapusan-kekerasan-dalam-rumahtangga- uu-pkdrt.html

- Balci YG, Ayranci U. Physical violence against women: Evaluation of women assaulted by spouses. J Clin Forensic Med. 2005;12(5):258–63.

Copyright @ 2017 Authors. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are properly cited.

mji.ui.ac.id